A zoonotic thorn in the flesh

COVID-19 has sparked a debate about whether public health should supersede food choices and local culture. We get into the (bush)meat of the matter

15 April, 2020•18 min

0

15 April, 2020•18 min

0

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Why read this story?

Editor's note: Six months from now, a village near the Indo-Myanmar border will celebrate an annual ritual Indians aren’t prepared to hear about. The village is Mimi, and it is home to three clans of the Longpfurii Yimchunger tribe. Nearby is the Sukhayap or “Lover’s Paradise” cliff, the 200 ft high Wawade waterfalls, and a spectacular complex of limestone caves. The Bommr people, one of Mimi’s three clans, are the sole custodians of these caves. They flock here every October for the ritual at least seven generations old, one that was established to appease ancestral spirits. It starts with the blocking of cave entrances. The clansmen stoke fires inside and wait as bats, thousands and thousands of them, either suffocate or are flushed out. The ones trying to escape are welcomed by the Bommrs, who use sticks to finish the job. Some men are bitten or scratched, others are exposed to bat guano, urine or saliva while treading in the caves. The clan handles the animals with bare hands before smoking them or using them as medicine. So integral are bats to …

More in Chaos

Chaos

Why UAE’s stability premium is under question

For years, the country has been insulated from West Asia’s conflicts. Six days into the Iran war, that status is under strain—and investors could be recalibrating.

You may also like

Business

Reliance’s battery plans run into a China wall

Mukesh Ambani’s $10-billion bet faces a harsh reality: much of the clean-energy stack still sits overwhelmingly in Chinese hands.

Chaos

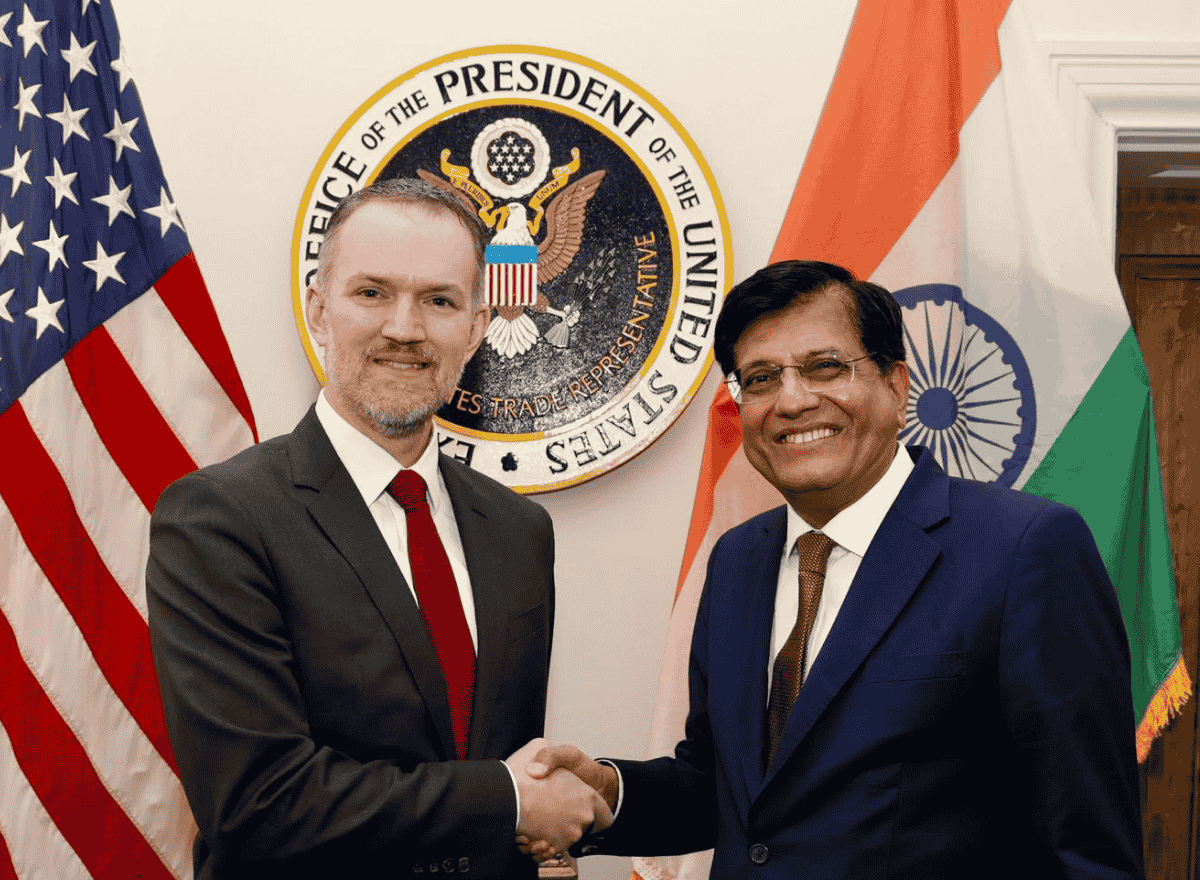

India needs to stop courting the US and look for a solid plan B

It’s never a good sign when your foreign minister needs a lobbyist to meet US officials. The recent events signal a breakdown in the Modi government’s ability to operate in today’s Washington through its own machinery.

Business

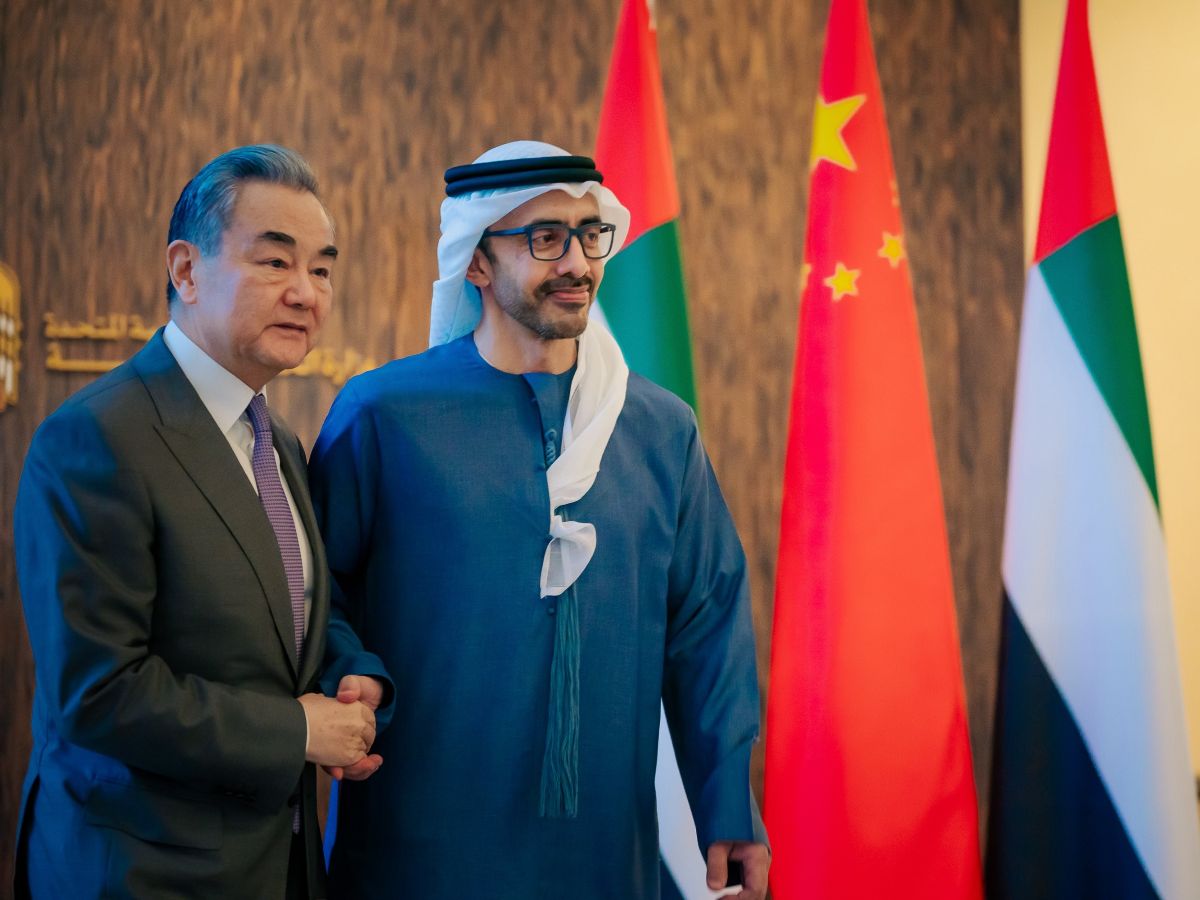

What China’s recent Middle East tour says about their ties

China’s expanding influence in the GCC region comes with its own set of opportunities—and constraints shaped by America’s influence in the Gulf.